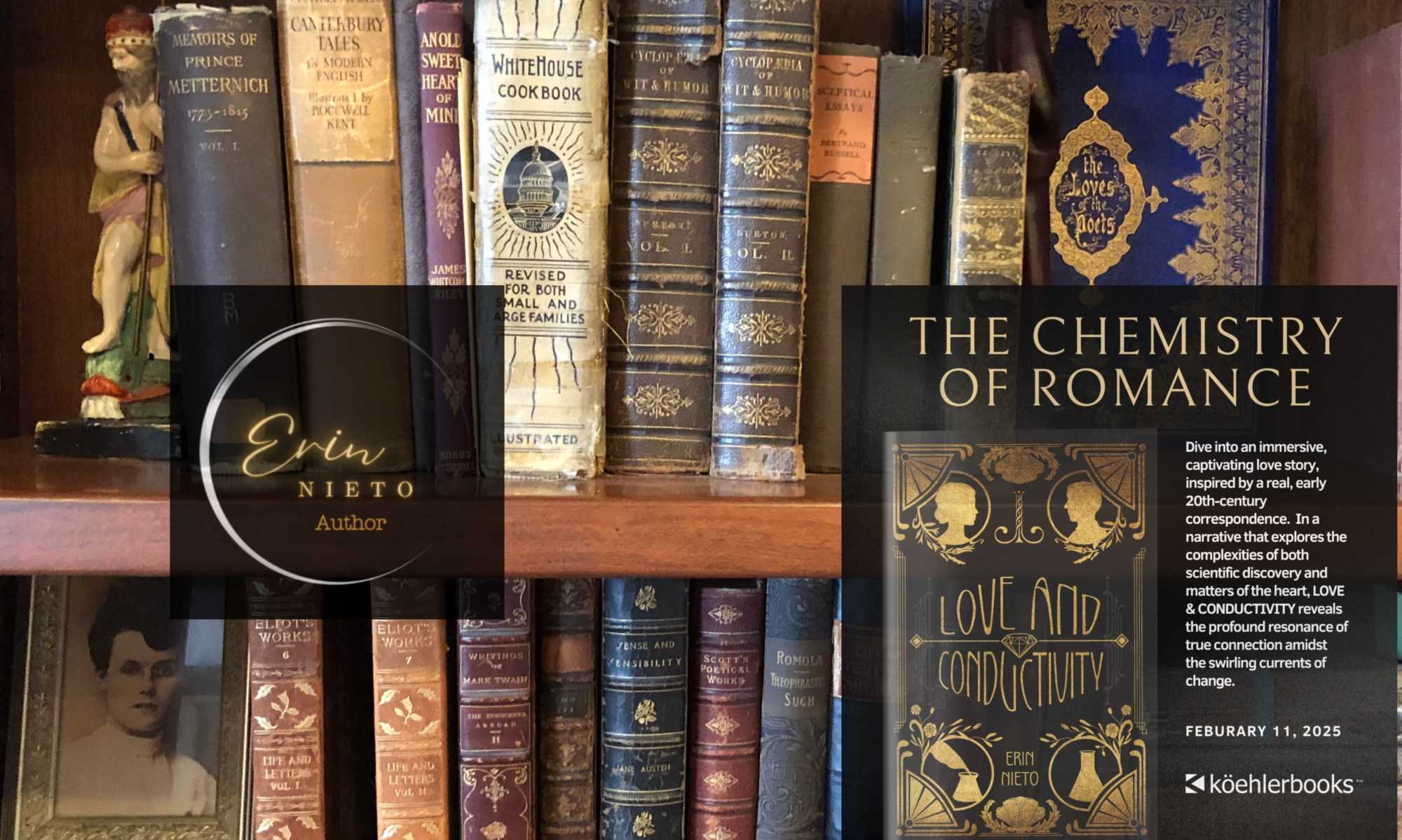

My novel, Love and Conductivity, is all about the beginning of a radiant, post World War I love story between Eleanor Morgan and Erwin Phipps. But here, let me introduce you to them in the way that I first met them: through what they left behind.

In my professional capacity as Appraiser of Art, I was often called in to evaluate collections of artwork in estates for which preparations were being made for liquidation. In this way, I met a lot of fascinating people … posthumously.

in January 2015 I was summoned to an old, prairie-style brick house in Urbana, belonging to a renowned but ailing 90 year old physicist; the staff organizing the house contents had been at work for several weeks and were ready to regale me with a breathless show and tell about the extraordinary family who’d lived there. I learned that the house’s owner was a second generation physicist, and that the house had in fact belonged to his parents, who’d lived there from 1938 until their respective deaths.

They gave me a tour of a chemistry laboratory in the basement; a mad collection of materials and gadgets and scientific instruments spanning all of the 20th century. The father had worked on the Manhattan Project and the son had worked at China Lake. The basement contained a cement-block bomb shelter, stocked with water and books and jewelry-making supplies. My head was spinning, and I hadn’t quite made it yet to the artwork.

As I eventually settled in to the task ahead, moving from room to room, past boxes and haphazard stacks and books and books and books, documenting the artwork contained in the house, Mary, the estate handler, sat stationed in the dining room with a grouping of boxes that had been brought down from the attic.

As I passed by her in my search for art, she held one hand over her heart, holding open a letter, yellowed with age. “I don’t know what I’m going to do with all of these old letters,” she said, “Just listen to this:”

She proceeded to read aloud the contents of the letter. It was addressed to the woman who would become the physicist’s mother, from his father, before their marriage in 1923.

To this day I do not recall the precise contents of the letter. It’s as if the unexpected beauty of the language and the depth of the sentiment shocked me, or drowned me, or sent me into another dimension entirely. I had never known written words exchanged between two private souls to contain such unrestrained intimacy before.

Mary stopped reading. I had my hand over my heart, too. “You see what I mean?” she asked.

I did.

Up to that moment, I had grown rather cynical in my life – about love; at least, about the distorted lens through which our current culture views it. And cynical about correspondence, which in my experience was largely formality with little place for sentiment.

Mary had two piles for estate items: To Be Discarded and To Be Priced For Sale.

Letters and items of a personal nature defaulted to the To Be Discarded pile. The physicist had requested not to be contacted in regards to the estate. There were no heirs. Mary had to choose.

“Humanity needs this.” I said. I didn’t know what else to say. I couldn’t, wouldn’t dismiss something like that as irrelevant to the rest of the world.

Mary decided to bundle the hundreds of letters and sell them at 2 bucks a pop. I attended the sale, relieved at her decision and hoping to find, amid the haystack of bundles, the letter which she read aloud. It seemed a treasure of the highest order; possessing me of a curiosity I couldn’t shake.

I blindly filled a shopping bag with bundles; a small dent in the haystack. I assumed – still cynically! – that the letter she’d read was the exception of the bunch. That the rest of the words they’d exchanged would likely pale in comparison. Boy, was I wrong.

After the sale, I began to read. And read. Randomly, at first, as the bundles were in no particular order; just soaking in the singular voices of these fascinating people. The letters were emotionally AND intellectually intimate; a very fine antidote to the toxic modern culture surrounding male-female relationships. And there was a “distanced nearness” effected by the letters – so close yet still so painfully out of reach – and the longing and hope and fear which must have resided in the margins.

Over the following months I began what would be a long process of understanding: I hunted down as many additional letters, post-sale, as I could (which, fortunately, was most of them!). I began to order them chronologically and transcribe them. I scoured Ebay for those re-selling estate items, and contacted re-sellers I knew to have attended the sale. I contacted their son (the now-90 year old physicist) and formed a friendship with him while I still could. I built an archive of artifacts, documents, photographs; I came to recognize two brilliant young adults, both somewhat lost in the world, both carrying past griefs, and the spark that they shared over the course of one day in 1918; how that spark went on, over time, to light a fire between them, and how that fire now lit up my own heart.

The transcribed letters, as they were the vehicle for this relationship, told me a lot. But not all. It became clear that it was the in-between-the-lines of their letters, is where the story lay, and that is exactly what I set out to write in LOVE AND CONDUCTIVITY.